How Has Redistricting Changed Since 2011

Nov 13 2020

There were a huge number of issues on the ballot in 2020: control of the U.S. Senate and House, legalization/decriminalization of marijuana and other drugs, potential restrictions on abortion and the gig economy, and, of course, the Presidency (i.e., decency and kindness among other things, according to the Biden campaign). Perhaps one of the most important things, even though it wasn’t always covered with much significance, was control for the redistricting process that is set to start following the 2020 Census. The 2020 Election was the last chance for voters across the United States to change the redistricting process in their state by altering the political control of their state’s legislature or by passing relevant ballot initiatives. With the redistricting processes and political power dynamics now mostly set, it is worth checking in on this crucial but often underreported process by comparing it to the redistricting dynamics in 2011.

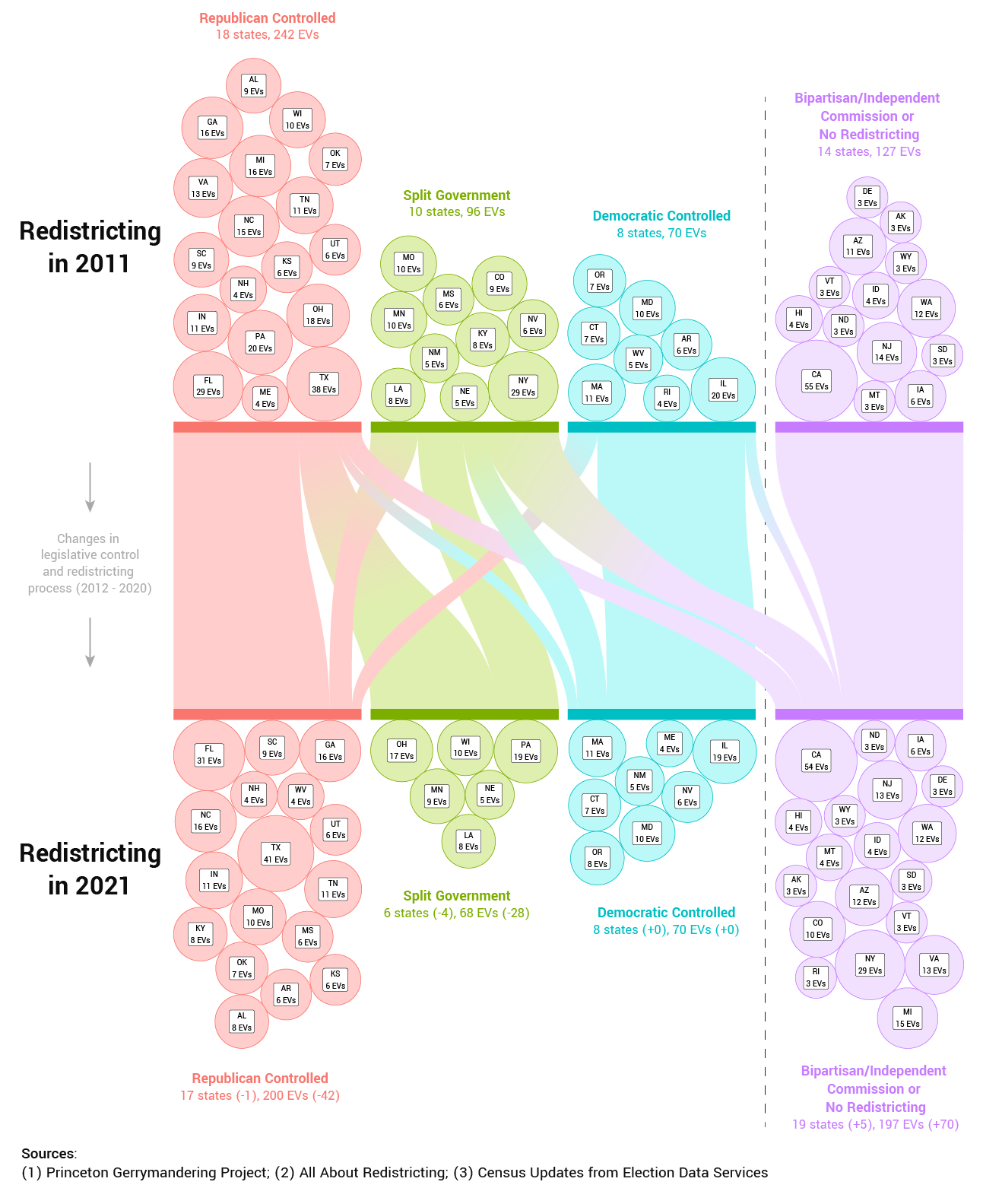

Coming out of the 2010 Election, after it became clear that Republicans had enacted a plan called REDMAP to take control of the redistricting process, Republican-controlled legislatures were responsible for redrawing nearly half of all Congressional districts. Meanwhile, Democrats were responsible for just 13%, leaving the remaining 41% of Congressional districts drawn by bipartisan or independent redistricting commissions (or come from states with only one at-large district). This split lead to rampant gerrymandering that allowed Republicans to win back majority control in Congress without a majority of the votes.

In the years following, after the implications of REDMAP had become clear, groups across the country gave new attention to making the redistricting process more fair both by balancing party control in state legislatures and transferring redistricting duties to independent commissions. We can see the latter appear in the chart above as five states (accounting for 70 electoral votes and 60 districts) shifted redistricting power away from partisan legislatures and towards some kind of redistricting commission.

Heading into the 2020 Election, Democrats were hopeful that they could take back some control in state legislatures, ideally shifting redistricting power to Democrat-controlled legislatures or at the very least split governments. However, Democrats performed poorly in legislative races across the country at both state and federal levels and are actually projected to have lost ground.

So these are the conditions under which the United States will redraw legislative maps, mostly unchanged for the sake of a decade. The fact that Democrats have not gained any majority control and have lost partial control in split governments in the past 10 years is not promising for Democrats hoping to get back at their Republican counterparts for the incredibly gerrymandered maps of the 2010s. But, while voters were not able to balance the scales in states where redistricting is run by the legislature, there has been a substantial increase in the number of states that use independently (or at least bipartisan-ly) commissioned maps, largely due to great work and ballot initiatives from groups across the country that understand the importance of fair maps.

While redistricting is certainly not the sexiest topic, if nothing else, the last decade has turned the public’s attention to what can go wrong when this process is left unchecked. With our eyes on the process, we can only hope that the maps of the 2020s are more fair than those of the 2010s. Hopefully it doesn’t just make for sneakier and more extreme gerrymandering…

* * *

Methodology and minutia

Control of the redistricting process was determined based on information from The Princeton Gerrymandering Project and Loyola Law School's All About Redistricting.

The number of electoral votes allocated to each state in 2021 is based on 2019 Census Estimates from Election Data Services, which shows AZ, CO, FL, MT, NC, OR, TX gaining seats and AL, CA, IL, MI, MN, NY, OH, PA, RI, WV losing seats. If Montana gains a seat, it will require redistricting (they currently only have one district) but their redistricting will be done by an independent commission. If Rhode Island loses a seat, they will only have one district, therefore not requiring any redistricting.

While many state legislature races are still undecided (as of 11/13/2020), most outlets are projecting that New Hampshire is the only state that will see any change in their state legislature, switching from Democratic to Republican control in both chambers.